With the increased environmental awareness and new energy efficiency regulations for buildings, owners, building operators, architects and engineers are constantly on the look out for new innovative products to meet the latest needs. A more efficient building envelope with better insulation is an alternative that can help meet new energy efficiency regulations for buildings. In such, additional insulation via an exterior insulated finishing system can be an appropriate solution for existing or new buildings.

In recent years, the lack of qualified labour and the increased cost of construction materials such as brick, stone and wood, have led to the research and development of new technologies for exterior finishing systems. Around 1960-1970, there was the introduction of the exterior wall cladding using rigid installation and acrylic finish, commonly referred to as EIFS. These systems allow for better thermal insulation, flexibility in architectural details (arches, keystones, cornice and corbel), and are offered in a variety of finishes and colours, all of which have contributed to the popularity of these systems since their introduction.

Until approximately the year 2000, this exterior wall cladding was generally composed of a rigid polystyrene insulation glued directly to the wall sheathing (plywood, OSB or other) and air barrier, without an air gap. In order to be efficient and functional, this single barrier system was required to totally resist water penetration, as there was no way to drain the water that would migrate behind the EIFS, in contrary to rain screen systems with drainage. In rain screen systems, the air cavity allows for water to be drained and air to circulate in order to ventilate the space (via weep holes and flashing). These systems can therefore allow for some water penetration by the porous masonry or by imperfections of the system. However, since the acrylic finishing system did not absorb water as masonry, it was judged unnecessary to have this air gap.

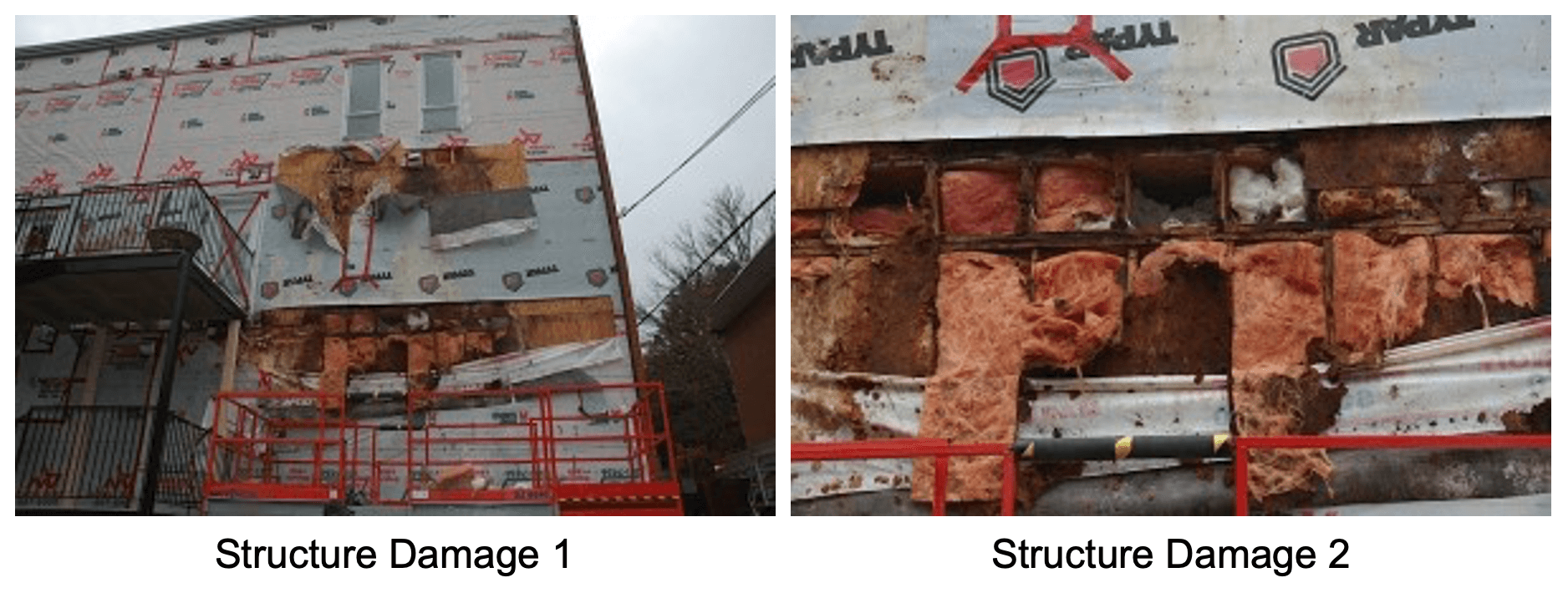

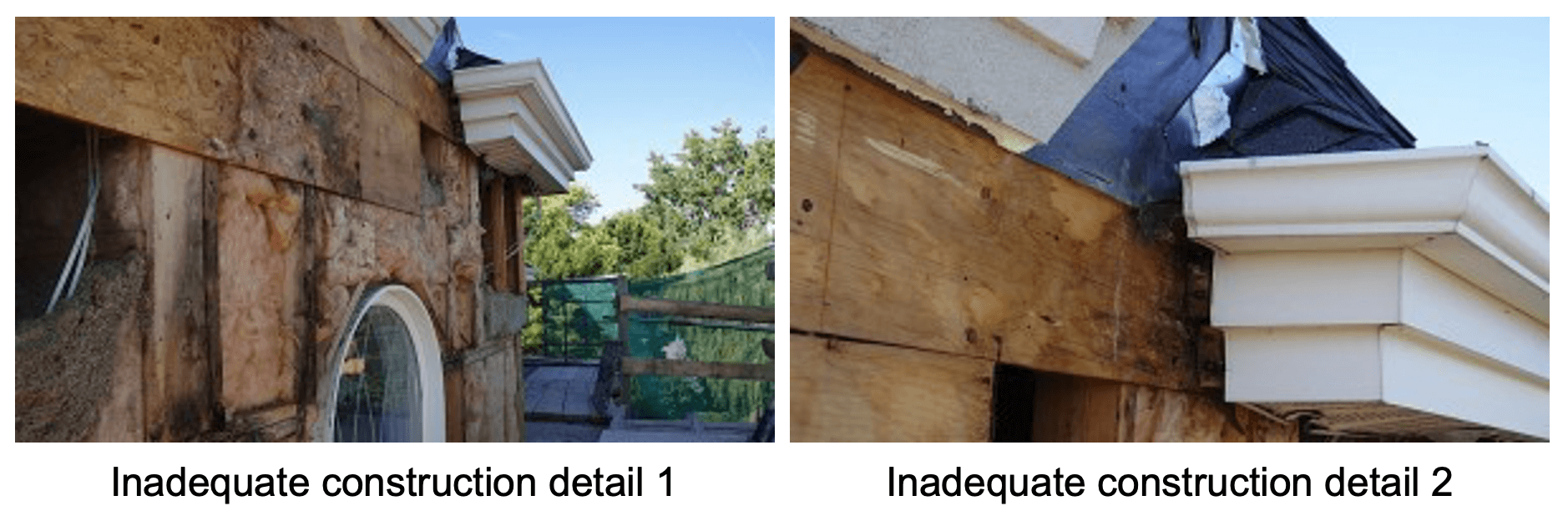

Throughout the years, many cases of water infiltrating behind the clad have proven otherwise. When the design of the building envelope is not perfectly detailed, or when the execution of these details is not impeccable, rainwater can eventually travel behind the clad. Also, with time, improperly sealed joints, lack of maintenance or cracks in the acrylic finish will also lead to water infiltration. Since these water infiltrations are generally not visible, they frequently last for years until there is even an indication of a problem. When the problems are identified, many wall sheathing and wooden structures are already heavily deteriorated.

Photographs 1 and 2 demonstrate the wooden structure and sheathing deteriorated due to water infiltrations by deficient caulking around the perimeter of the windows. The structural damage visible on Photographs 3 and 4 results from an inadequate architectural detail at the junction of the roof and wall. In both cases, these deficiencies have allowed for repeated water infiltrations for years, resulting in a severely deteriorated sheathing and structure since there was no exit for the water or ventilation for drying.

According to many technical documents from various manufacturers of these exterior insulation finishing systems (EIFS), the insulation panel was adhered directly to the substructure, up until the year 2000. However, in the more recent editions of these documents, we observed a noticeable change in the method of installation of the systems, where many systems now include drainage and an airspace between the sheathing and installation (generally provided with a grooved insulation) and perforated mouldings and flashing at the bottom of the wall allowing for drainage. This space will therefore permit for water to drain and provide ventilation for humidity to be dried within the system. The noticeable change in the method of installation of EIFS is an indication of the magnitude of the problem. Also, the Canadian standard for EIFS CAN/ULC-S716 should be part of the 2015 edition of the National Building Code of Canada.

Conclusion

In conclusion, even though the damage to the structure is gradual, the cause and origin of the problems is typically from a construction defect or an inadequate concept for this type of clad. In many cases, legal recourse is possible.

If you have any questions or would like to learn more about this topic, please contact our Structural & Civil Engineering at 877 686-0240 or info@cep-experts.ca